The different prosthetics the soldiers would wear.

WWI was no doubt one of the most horrific times in human history; the death toll and carnage were beyond belief, and most of the dead and injured were young. People who had hardly left their mother’s apron, now broken men with disfigured faces. There were thousands of them, and the ones who survived were nothing more than a shell of the person they used to be prior to the war. The ones who stayed behind carried the heavy burden of continuing with work and taking care of family, alone, while worrying about their loved ones. No one left this war unscathed.

The doctors and nurses, as well as volunteers, had their hands full, but there was only so much they could do to help these poor men—especially if they were to rely on old techniques. So many had to live with a prosthetic attached to their face, but once those masks were removed, they could stare directly into their soul. It was time to think of new groundbreaking ways to treat these men in order to bring a ray of hope, albeit small, into their future. Surgery could never repair the psychological damage or dull the ongoing physical pain they would suffer for the rest of their life, but a better face would make their life a bit more tolerable, perhaps a bit easier to blend back into society. This was when Dr. Harold Gillies began to preform skin graft surgery on British soldiers.

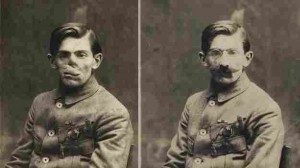

WWI veteran with and without his mask.

The genesis of plastic surgery took place in England, a fact that would probably surprise most people, specifically because America is usually credited with exaggerated use of plastic surgery for vanity reasons more so than anywhere else, and South America is a close second. The doctor is also credited with employing an innovative technique of surgery called “tubed pedicle,” which used the patient’s own tissue to reconstruct the face in order to lower the chances of rejection by the body. Dr. Gillies wanted to do so much more than only restore minimal function to the face; he was adamant about restoring their appearance to what it was before the injury or as close as possible at least. For this reason he used the services of artists and sculptors who would create a plastic cast of the expected post-surgical result. One such sculptor was Kathlene Scott, a wife of an arctic explorer. World War l, although tragic, was the first time that women shed off their constricting Victorian garb and joined the workforce in full force.

There’s nothing as ugly as war, it’s destructive and inhumane, yet war is what also brings out humanity in so many people. Another irony of war is that it’s the context from which so many of our modern-day advances in medicine and innovations have stemmed from. It was a case of necessity by numbers; these days the terrible injuries suffered by soldiers are almost 90% treatable, because of those early days of war.

Plastic surgery performed by Dr. Gillies on William M. Spreckley, a WWl veteran.

Dr. Gillies’ work paved the way for the first modern center for facial and plastic surgery at the Queens Hospital in Sidcup, England, in 1917 and by 1920 he published the first book about plastic surgery. He was one of the first to perform a sex change operation and will forever be known as the Father of Plastic Surgery. These days, plastic surgery is used for many other reasons other than just necessity, and it does raise a few interesting questions. In the early days of plastic surgery, the belief was that good looks were necessary in order to help the soldiers blend back into society, and today the same sort of mind-set prevails, even though we’re not talking about war injuries and more about a specific look that is deemed perfect by most, and necessary in order to achieve happiness. They are prepared to change their looks even though surgery is dangerous and painful, and results can never be guaranteed.

I don’t know the motives of every man or woman who opt for plastic surgery in their attempt to enhance their looks, but listening to what plenty of men and women have had to say about the topic, it’s easy to surmise that some are motivated by their need to please the other sex, and others see it as a necessity in order to boost their self-esteem. If they look “perfect,” what follows is happiness. The only way to achieve this happiness is by changing the shape of something on their face or body, and if these surgeries are readily available to anyone then why not pursue this option?

What puzzles me most though is that since World War l, when women had finally joined the workforce, wore pants for the first time in their lives, followed by their right to vote a few years later—they’vebeen making great strides in their advancement in terms of equal rights in a male-driven society. It’s strange to think that there’s still a need to conform to a certain look. Then again, if you look at how women’s bodies have changed hand in hand with their fashions, then you understand that all this is nothing new, and certainly not part of Western ideology alone.

One can say that war had paved the way for Timmie Jean Linsey, a 30-year-old factory worker who was so unhappy with her B-cup breasts that she did what no person had done before: she underwent the first breast enhancement surgery in 1962. What followed next you already know.

Nobody’s perfect! Success in no way depends on looks…

By the way I loved the excerpt from the book and I can’t wait to order! 🙂