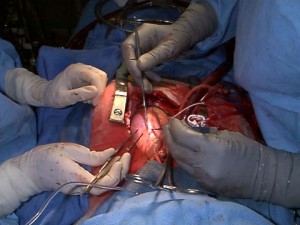

Leon performing heart surgery.

On this blog I have taken the time to expound on the human body as seen and understood throughout the ages, mainly because I am in pursuit of accepting the aging process with a different set of eyes—a different perspective. I’ve already posted a poem written by my grandmother about aging, and today I’m posting a poem written by my father, Leon Levinsky, not so much about aging but very much about an aspect of it that I have not made my main focus. Heart disease is a problem that many experience at a certain stage of their life; there are so many ways to prevent heart disease from happening in the first place, and yet there is so much ignorance revolving around this important health topic.

Usually, when we hear about surgery, it’s solely about the patient’s experience; what makes this poem so unique is that rarely do we get a glimpse of what goes on through the surgeon’s mind as they engage in this life-threatening procedure. Leon’s poetry shows that there is more to him than meets the eye—usually very shy and mostly reserved—this poem gives you a rare glimpse at a man who is very much an artist as well as a serious surgeon. He demonstrates a knack for being able to draw you into his world by navigating through a complicated procedure, yet artfully shuttling back and forth between technical jargon and grisly details that allow you to live through his experience of bringing a heart back to life.

This has given me a renewed appreciation for what he does. However, I have to say that I still scratch my head when thinking of all the times I would see him handing my mother one of his socks for mending; I mean, the guy knows how to sew up a heart, and yet he could never fix a hole in his own sock!

As a heart surgeon’s daughter, I grew up privy to detailed conversation around the dinner table, watching the way my father would react in emergency situations—hardly having him home for that matter—I am proud to say that Leon Levinsky represents a special breed of surgeons. I remember the odd neighbor that would stand outside our door, waiting for my father to arrive home from work—my father tired, exhausted—yet, still sensitive enough to listen to anyone’s medical problems and resolve their issues. I’ll never forget the day that an old Russian woman (I think she was Russian, but not sure), knocked on our front door holding a large box filled with oranges in one arm, and in the other, grasping the hand of her young grandchild. Leon had operated on her husband and saved his life, and she insisted on expressing her gratitude by traveling from her home, having ridden a few buses, and trekking up the hill where we lived, in order to come bearing oranges for my father. As I peeked through the kitchen door, I could see the woman’s gold teeth glimmering through a bashful smile. My father would immediately make anyone in his presence feel comfortable, so the nerves soon melted away. As she sipped from her cold drink and nibbled on a few biscuits, Leon learned about each one of her family members.

There were some unpleasant memories as well, like a family who had threatened to kill Leon because their father had died on the operating table; it was not my father’s fault, but nevertheless, he found himself having to hide from them out of fear for his life. When there was a knock on the door one evening, and we opened it, forgetting about Leon’s warning—it happened to be one of our friends—but regardless, he yelled at us for almost getting him killed. Usually, when a heart operation is successful, people tend to thank God but when things go wrong it’s the surgeon’s fault. A few years ago when I gave birth to my son Jack, the anesthetist in the operating room yelled at me for shaking too much before I was given an epidural. I was completely shocked by his mood and temper. Then, while lying down awaiting the surgeon to begin the C-section the anesthetist yelled at one of the nurses for not introducing herself to him in “his” operating room. The poor nurse looked just as shocked and terrified as I was. My IV popped out of my vein mid-surgery and I’ll never forget how brutal he was in pricking the back of my hand over and over again to get it back in, at which point I began to throw up and he looked completely infuriated with me. My son’s birth will always be tainted by that doctor’s terrible bedside manner, but fortunately I have some good experiences as well with nice doctors. And most important, I have wonderful memories of my father’s patients whom I’ve met occasionally over the years—giving their praise of how sensitive and caring Leon had been during their time of need. Now it’s time to learn about how surgeons develop wrinkles.

“A Heart Operation”

A scalpel slices skin

In the midline

A saw divides the sternum

With a sickening sound

Bleeding is stopped

A retractor is wound open

There is a hubbub

In the operating room

Christie is harvesting a vein

From the leg

While I preside

At the chest

Like the captain

Of a ship

Like a captain of a ship.

Joe administers anesthesia

So the patient is unconscious

And will not be aware

When his heart has stopped

Sylvia hands over instruments

Never has to be asked

Always the right one

So reassuring for me

Sylvia in perfect sync with Leon.

Linda sits at the pump

A giant machine

Of tubes and cylinders

Instead of the beautifully designed

Heart and lungs

Amy is circulating

Darting around the room

Music in the background

Pagers are beeping

Phones are ringing

Gossip is exchanged

But there is a person

Beneath the drapes

For whom this

Is no routine day

It is the second most

Important day of his life

The first was his birth

Concentrating on the task.

I am oblivious

To the surroundings

As I concentrate

On my task

To fix this heart

And bring it back to life

There is a puff of smoke

As I use the bovie

To open the pericardium

And expose the heart

In all its sick glory

Covered in a layer of yellow fat

With red arteries and blue veins

Barely discernible in the depths

The heart covered in a layer of yellow fat.

From the front the damage

Is not so evident

But then I lift the heart

And my own heart

Misses a beat

As I realize

That this one

Is too heavy

Too thick and sluggish

With a pale patch

At the back

Testament to muscle

No longer alive

I inspect the arteries

I inspect the arteries.

That need to be bypassed

I have made my plan

Purse string sutures are placed

On the aorta and atrium

A knife jabs a hole

Blood spurts and

Cannulas are inserted

And connected to

The heart lung machine

Now Linda is alert

As I tell her

“Start the pump”

Purple blood exits the heart

On its way to the machine

And is miraculously transformed

Into red blood

To be pumped

Back to the aorta

And so to the brain and other organs

“Start cardioplegia” and now

The heart slows and stops

Under the influence of potassium

Ice slush is poured on the heart

To lower the temperature

Fifteen degrees that’s good

Three pairs of hands.

There are now three pairs of gloved hands

Over that small space

One pair holds the heart

Now lifeless

Like a slab of meat

While I use a knife

To make an opening

In an artery,

One or two millimeters

Another pair of gloved hands

Assists me as I join

The end of a vein

To the opening

Using a sewing technique

I learned in this very hospital

Over thirty years ago

From my teacher, George Schimert

Who said to me

“Leon, handle the heart

As you would a woman’s breasts

With gentleness love and respect”

Handling the heart as you would a woman’s breasts.

And reflect on the Man beneath the drapes

Essentially he has no heart right now

And his family waits outside and wonders.

The position of the heart

Has been changed many times

And I have completed two ,

Three or four anastomoses

The last using an artery

Prepared from the back wall

Of the chest

The internal mammary artery

Supplies blood to the breast.

So George was right.

Stitching up the patient.

I use a thread

Not much thicker

Than a human hair

But to me it appears

Like a piece of string

Through my magnifying loupes

Warm blood is perfused

To the cold heart

The clamp is released

And I look with awe

As the heart slowly starts beating

And resuming its pumping action

With a twenty degree twist from

Stem to stern

The machine is stopped

The heart is on its own

Reborn, stronger, healthier

Supporting the brain

Kidneys liver intestines

I am relieved and breathe

A sigh of relief

Slowly the chest is closed

Using steel wires to bring

The two sides of the sternum

Together and then suture

The fascia and skin

The drapes are removed

Surgery is over.

Surgery is over

I remove my gown

My shirt is drenched

With sweat from the heat

And emotion and relief

I change my shirt

And go to tell his wife

That all is well

Powerful poem.A Dr. with a big heart.